Images of the work described in this piece can be found below the article in the attached slide show.

My brother Jules turned 30 this past Saturday so it was the perfect excuse to grab some coffee and, braving the January cold, head to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It was a family tradition in our household that on one’s birthday you could be taken out of school and my father would take you to a museum. It felt right to have the old man take us to the museum once again and, what followed, was an inspiring, fun and moving afternoon. We hadn’t been to the Met in years and never together. We had chosen the Met because the once-in-a-lifetime exhibition, Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer was still there, consisting of the largest collection of Michelangelo’s drawings, sketches, notes, poems and cartoons ever to be displayed. Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), was a towering genius in the history of Western art, so towering he was called “Il Divino” in his lifetime. Yep, so immense was the master’s talent he was called “the divine one” while he walked the Earth. How could we approach something so vast? How could we find the artist and, in turn, ourselves in works so revered they seem like monoliths of an unapproachable genius?

I have long had a fascination with Michelangelo, the sculptor who would chisel The Pieta (1498-9) before his twenty fourth birthday, for a variety of reasons. Michelangelo was deeply, deeply Catholic. He suffered from massive guilt over his sexual identity, a father who always begged for money and demanding benefactors whose commissions would exhaust him emotionally and physically. Some of his best known self-portraits portray this anguish. He is present as the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew in the ghastly and powerful The Last Judgement (1536-41), the aged Nicodemus tenderly holding the body of a dead Jesus in The Deposition (The Florentine Pietà) (1547) a sculpture that barely survives — as his letters reveal, he took a hatchet to his own face and limbs. A complicated guy. All of his emotion, pain, joy and desire are in his drawings and perhaps in no better way reveals that behind the stoic image of the severe master is the portrait of a tender artist, figuring things out, playing and thinking. In these hundreds of drawings Michelangelo is finally present.

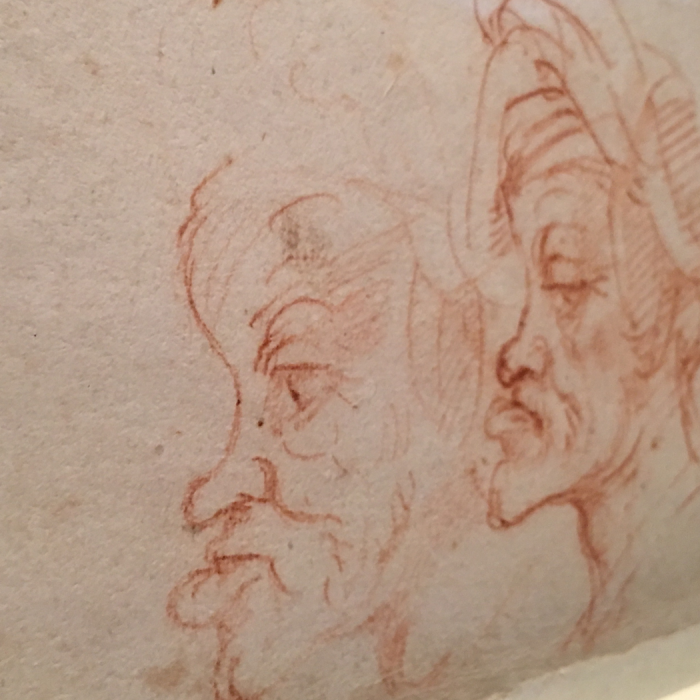

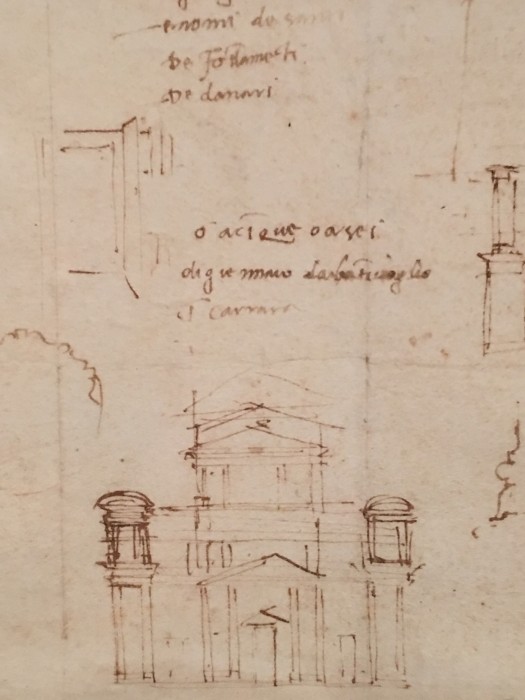

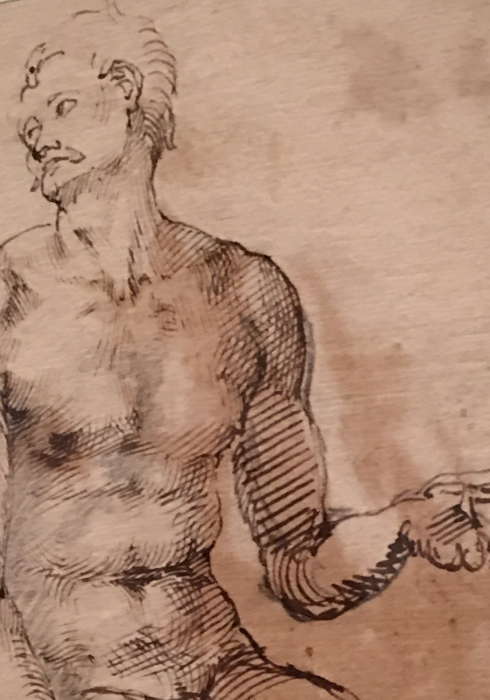

The show features several sculptures of varying completion. While Michelangelo always considered himself a sculptor first, it is in his drawings where we get the most intimate portrait. Divided into stages of his life, the gallery opens with the drawings of the prolific art student whose copies of medieval painting rival the paintings themselves. In a brilliant move, the organizing curator of the exhibition, works by contemporaries and influences also hang in galleries to provide context. Then, we have the brash creator of The Pieta (1498-9). What follows are drawings from his storied career. His sketches for Pope Julius II’s tomb show the artist in fluctuation as economic and political constraints kept changing the piece. His studies for the Sistine Chapel’s Ceiling (1508-12) and The Last Judgement show a more tender approach compared to the epic scale of the final works. His “Study of the Libyan Sibyl” becomes emotionally more connected to us, the viewer, as is the face of his study of “Young Man in Bust Length in Exotic Costume.” The portraits seem to be of real people (as surely they were real models) as opposed to dispassionate paintings. One of my favorite moments is his “Study of a Seated Nude,” most certainly a fellow artist or student in his workshop as the quick sketch offers us the rare portrait of the actual model, complete with mustache and rolled belly, before he will be recast in the neoclassical style so famous in the period.

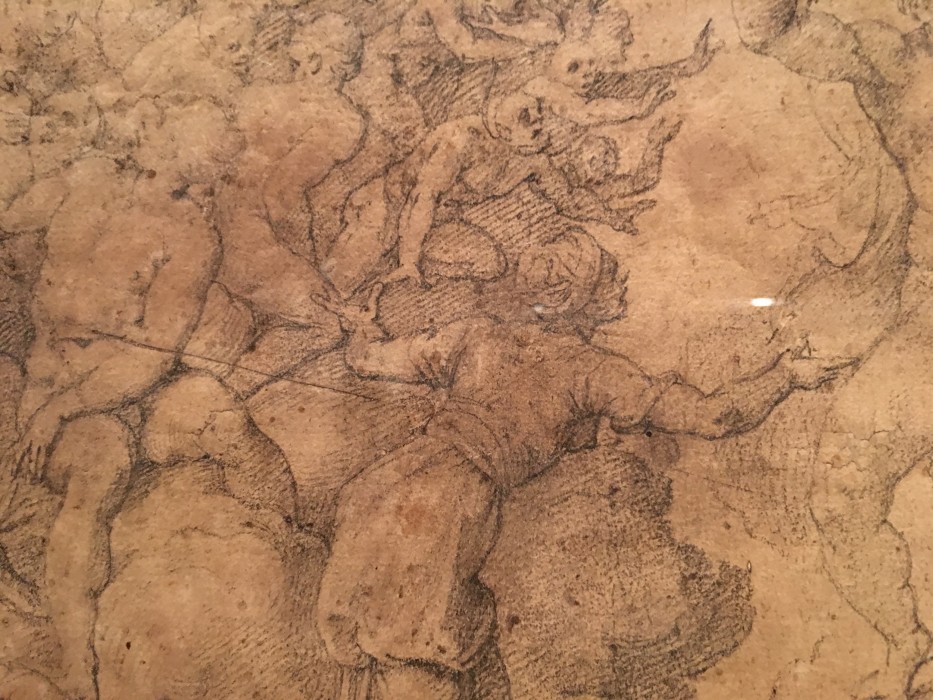

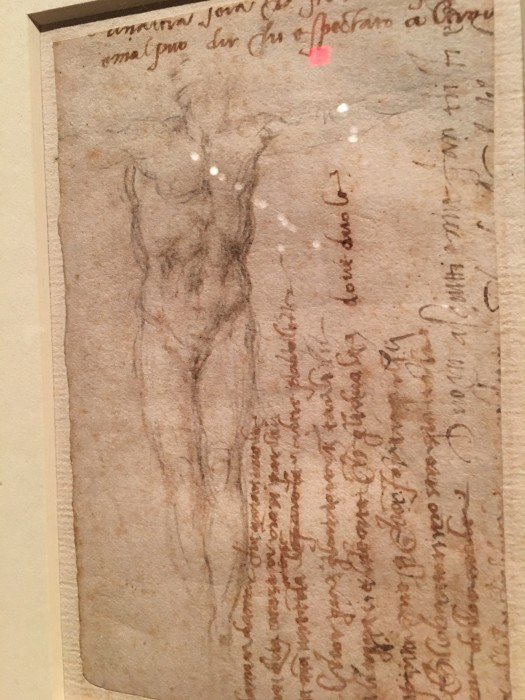

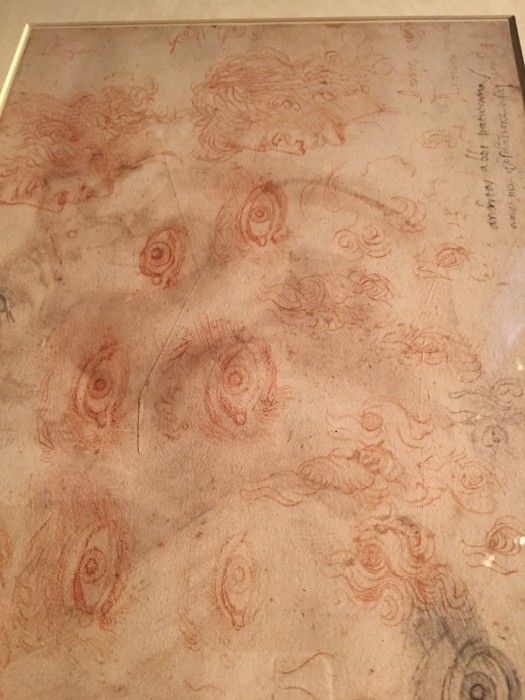

There is also the playful Michelangelo that sketches the grotesque caricature of an older woman for a student to copy next to his “Exercise Sheet: Drawing Lessons by the Master” and, my personal favorite part of the show, the master as teacher, we see the surreal exercise sheet of yet another student drawing the detail of a human eye after his teachers examples, the two different hands side by side in different inks and in Michelangelo’s own penmanship he writes on the student’s sketch pad, “don’t forget to be patient with yourself.” It is in those moments that the drawings come to life not as just pieces of work or fallen scraps from a brilliant mind but as documented evidence of an artist at work. These small personal moments continue. In his “Study for Christ on the Cross” he sketches a faceless crucifix and scribbles the idiomatic, ironic, rhyming (in Italian) lines: “another evening because this evening it is raining / and one can say badly, who is expected elsewhere,” with the sheet rotated, Michelangelo drafts a poem, which he then almost entirely cancelled, his melancholy is palpable. In other studies, for example, the artist is thinking quite boldly of the role of the saints and heroes of the Bible. In his “Composition Sketch for the Upper Parts of the Last Judgement,” his Mary, back turned, is pleading with her Son to rescue the damned, far from the final portrait we find of Mary, enveloped quietly in her Son’s presence. Whether it is the artist in a formal tone, sketching the heavy lidded, “Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi” to the visible movement of his “Archers Shooting at a Herm,” I can’t express how much fun it was to journey through the master’s notebooks. It reminded me of a time I snuck down to my father’s basement studio, cracked open his sketch book and peered into the mysterious images that I couldn’t then comprehend.

Michelangelo died in 1564 in his eighties surrounded by sketch after sketch of drawings, most of the crucifixion, to the very end hoping to draw his way to heaven. Later that spring, of that same year, William Shakespeare was born.

Run, don’t walk to see this show.