Why would someone who has lived nearly their entire life disabled, at the mercy of doctors’ surgeries, in need of a variety of technical apparatus like walkers, braces and wheelchairs, that lived through great physical pain, hope that when they die, they would enter into the kingdom of God still disabled? Such was the case for Nancy L. Eiesland, the sociologist, theologian and author of the groundbreaking book The Disabled God: Toward a Liberatory Theology of Disability. Eiesland, like many, felt that without her disability she would “be absolutely unknown to myself and perhaps to God” (The New York Times, March 21, 2009).

Here in our blog we hope to have culture guide us. It is the films, novels and paintings that we hope to use as our guide, as we search for our own Arcadia. How can a curious and thin volume of theological non-fiction help? It may seem off-putting, unforgivingly dry, but boy, is this book alive!

Throughout Church history we have acquainted wellness with holiness and disability as an outward sign of some spiritual aberration. Certainly the ancient Palestinians thought this. You may even remember the disciples asking Christ, “Rabbi, w ho sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2). Jesus’ answer, while deeply compassionate, seems to back this sin as disability of “sin-disability” as Ms. Eiesland names it, answering, “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be made visible through him. We have to do the works of the one who sent me while it is day. Night is coming when no one can work.While I am in the world, I am the light of the world” (John 9:3-5).

ho sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2). Jesus’ answer, while deeply compassionate, seems to back this sin as disability of “sin-disability” as Ms. Eiesland names it, answering, “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be made visible through him. We have to do the works of the one who sent me while it is day. Night is coming when no one can work.While I am in the world, I am the light of the world” (John 9:3-5).

Ms. Eiesland takes that notion on in a bold way writing, “As long as disability is addressed in terms of the themes of sin-disability conflation, virtuous suffering, or charitable action, it will be seen primarily as a fate to be avoided, a tragedy explained, or a cause to be championed rather than an ordinary life to be lived” (The Disabled God, 75). That’s a perspective from a lived experience!

There is no doubt that there is a long and proud tradition of Christians and Jesus himself helping the disabled and sick, but as Ms. Eiesland points out, for the disabled “to be rescued from the body is merely another word for death” (43). That may seem harsh or overly critical to the able-bodied, but Eiesland is on to something because all of us, no matter how healthy or holy, will ultimately succumb to a time in our lives that we will not be able-bodied and in her theology we can accept that not as punishment but as a natural and full part of life as well.

That feeling liberates me. When my mom was dying of cancer my siblings and I hated the often outlook that disease and disability are somehow the shadow side of able-bodied life. In often militaristic language we kept hearing that our mother was “a fighter” and we should wage “war” against the disease. I believe my mother was a fighter, but she did not lose to health, and much of the ending time in her life was just that — life!

Eiesland goes further and this is where she is at her most shocking, brave and thrilling. Exploring the many paradoxes of Christian symbolism (the first will be last, the servant will be exhausted, etc.), she comes to realize that God Himself is disabled. Contemplating the story in Luke 24:36-39 in which the risen Jesus invites his disciples to touch his wounds, she contemplates the centrality and completeness of the resurrected Christ, writing that “in the resurrected Jesus Christ, they saw not the suffering servant for whom the last and most important word was tragedy and sin, but the disabled God who embodied both impaired hands and feet and pierced side and the imago dei” (99).

In Advent and Christmastime we celebrate the mystery of Emmanuel or “God is with us.” In the resurrection we celebrate the God who is like us and embodying us. As Eiseland beautifully notes, “God appears in the most unexpected of Bodies” (100).

Nancy Eiesland died in 2009 at the age of 44, not of her dishabilles but of a genetic lung cancer leaving behind her parents, husband and child. In her shortened life she gave us her unimaginable brilliance and God’s grace shines through her work. It knocked me over.

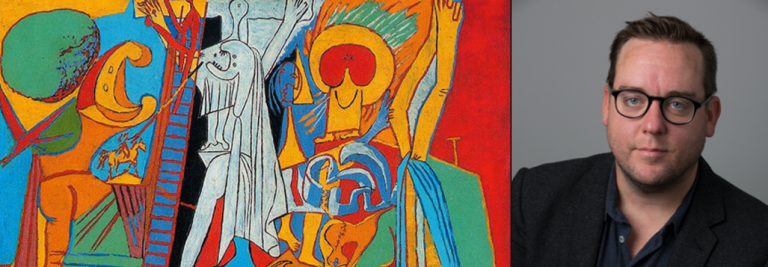

Cover painting: Pablo Picasso. La Crucifixion, Musee Picasso, Paris. Copyright photo: Reunion Des Musees Nationaux.